In some ways the New York Times is the BBC of print journalism: dominant, revered, imperious, sometimes bathed in irritating self-congratulation. But it is also, inevitably, an obsessively observed leader in the hideously difficult business of moving from newsprint to digital screen. If the Times can make it, perhaps others can. If the Times fails, then newspaper companies everywhere can start to despair.

Which makes its latest health check (from an officially appointed team of its own journalists) seem very important. Three years ago, a first “innovation” team report plumped for digital integration and chose subscriptions – paywalls rather than advertising free-for-alls – as the chosen survival route. Now “Our Path Forward” marches ambitiously down that road.

“We now have __more than 1.5m digital-only subscriptions, up from 1m a year ago and from zero only six years ago. We also have __more than 1m print subscriptions, and our readers are receiving a product better than it has ever been …”

But such success isn’t enough, apparently. Transitions never go fast or far enough – unless of course they go too far, too fast. The danger down this trail is a relentlessly balanced tour of Cake-and-Eat-It territory. “We need to reduce the dominant role that the print newspaper still plays in our organisation and rhythms, while making the print paper even better.”

Brothers and sisters, that’s pure self-delusion. Print is a meal prepared to a set deadline, emerging from ovens at a magic moment. Digital is a constantly changing 24-hour buffet. Make print assemble its menu from that buffet and, inevitably, there’s a weakening of focus. Not fatal perhaps, but not offering something “even better”.

And, indeed, the most interesting chunks of Times future shock come at the interstices where standard print wisdom needs radical rethinking. “Our largely print-centric strategy, while highly successful, has kept us from building a sufficiently successful digital presence and attracting new audiences for our features content …

“The Times’s current features strategy dates to the creation of new sections in the 1970s. The driving force behind these sections, such as Living and Home, was a desire to attract advertising …

“Today, we need a new strategy … Our approach has kept us from building as large a digital presence as the Times brand and journalistic quality make possible, and kept us from making our print sections as imaginative, modern and relevant for readers as they could possibly be. To be blunt, we have not yet been as ambitious or innovative as our predecessors were in the 1970s.”

All of which hovers on the brink of an essential point. Simply, in terms of range or ambition, the whole idea of a print newspaper (as honed four or five decades ago) may not be fit for purpose in an online world. Simply, the two concepts are different – one rooted in packages from the 70s, the other just one click away. Simply, editors may not be able to ride two horses together.

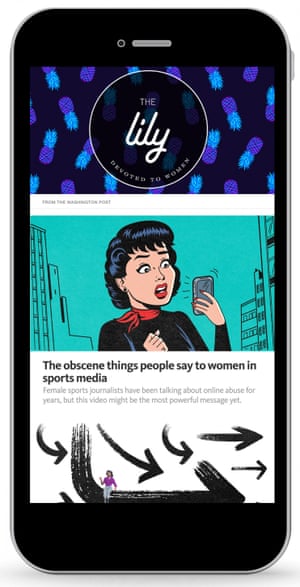

Look around at the digital news initiatives that are making the weather in 2017. The Washington Post (prime competitor to the Times) is launching the Lily – a quite separate site of Post news re-edited for female millennial consumption, intentionally young, not old. The founders of Politico have just launched Axios, a site that gives you the news at pace (and added depth as required). And, of course, there’s the massive Mail Online, which is nothing like the Mail on a newsstand. In short, you need an angle, a particular selling point: you don’t need the full legacy treatment.

A new report from the Reuters Institute on media upheavals in 2017 predicts more print papers will follow the Independent and go online only. But does the digital shade of the vanished print Indy demand that City writers follow business or football correspondents watch touchlines from Manchester to Southampton? Doesn’t the drought of print advertising mean that sports pages – geared to young men – have lost their former pull? Such pages anyway barely exist in much of Europe, where defined sports dailies do the basic job: why not the same pattern online henceforth?

In New York Times terms, it doesn’t matter if news sites, in the immediate future, don’t offer every ancestral reader service. On the contrary, from the Lily to Axios, the name of the game is choosing news with a style and an audience: concentration. That doesn’t mean that print New York Times, with its million subscribers, is dead and soon to be buried. Just the reverse. Separation plus concentration. The imperative is to reinvent digital subject areas and sites from scratch, not pretend that print’s structure and subject choices still rules OK.

Media advertising needs “new skills, talents, technologies and substantial fresh investment”, according to Mark Thompson, once BBC director general, now New York Times boss: a man to bring two worlds together. But as Thompson charts this future with its “unified approach” in his essay for Last Words, a comprehensive series of such examinations from Abramis published last week, does he ever think that equally different imperatives apply for the stuff that runs between the ads? The stuff we call news.

• A sign of dismal times: BuzzFeed hires an ace reporter from the Wall Street Journal and announces his unique new brief: covering relations between the Trump administration and the press. Yes, yes, but what’s his job title going to be? Silence. Though you guess senior correspondent for incestuous affairs would do pretty well.