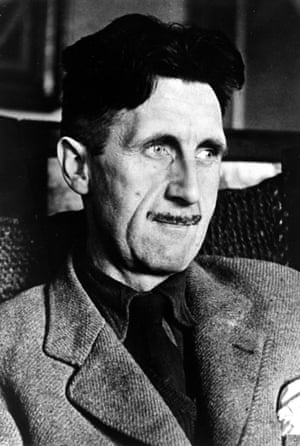

In 1944, George Orwell looked back on his political commentary and sighed. “In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer.” If Orwell could think of himself as a mere pamphleteer, where does that leave everyone else who produces comment pieces?

Reading through national newspaper files offers few comforts. Indeed, nothing brings home the futility of political writing __more starkly. It’s not just that virtually all of the writers and many of their targets are now forgotten. The arguments commentators make are generally as predictable as the speaking clock. Pick a newspaper of the left or right from the 20th century, or click on a left- or right-wing website today, and you can prophesy what a writer has to say before he or she has said it.

At the Observer, where Orwell wrote in his last days, there is a faint flicker of hope. We do not face the commercial and propaganda pressures to pander to our readers, because we are not sure who you are. Once you have said they are intelligent and literate, all we can add is that they are “liberal”: a label that is so capacious it includes everyone from moderate Tories to socialists.

Far from being a handicap, ignorance can be a blessing. We cannot address you as if we are fellow members of a religious sect or private club with commonly agreed taboos. We must work on the assumption that many of you will start by disagreeing with us. As a result, the Observer has been a home for writers of great polemical clarity. They have assumed that they must convince those who are politically disposed to dislike them.

Clear writing is not necessarily great writing. But clarity is the essential quality of writing that is trying to change a reader’s mind. No one will put Louis Blom-Cooper’s arguments in the Observer against the death penalty in the 1960s in an anthology of great English prose, for instance. But Blom-Cooper answered every objection a supporter could have raised. He wasn’t preaching to the choir, and ignoring the best points of the other side, but seeking to convince the sceptical. By the time he had finished, the case for the death penalty was dangling from the gallows.

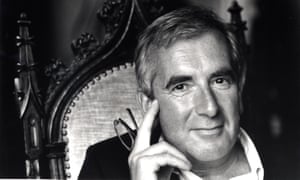

Similarly, I am sure that Robert Harris will be remembered for his books, rather than his journalism. But when he was an Observer political columnist he took conservative illusions about Margaret Thatcher seriously before he shredded them. She was concentrating power in her own hands rather than dispersing it, as she pretended. Far from reducing the size of the state, all her privatisations failed to dent public spending in the slightest. At every stage, he showed he understood how Conservatives thought before showing them how they were deceived.

The urge for clarity produces a reaction against obscurantism, which since Jonathan Swift, has been a part of the English polemical tradition. Academic writing, management speak, and the assembly-line cliches of the right and left have never found a home here. To be anti-academic is not the same as being anti-intellectual. Bertrand Russell was an Observer contributor, after all. But Russell’s school of analytic philosophy was concerned above all with conceptual clarity. To put it as gently as I can, intellectuals and politicians who do not share his passion for precision are unlikely to have the comment desk return their calls.

The tension between believing you are right and fearing that readers will not listen also produces the anger that powers the best and, indeed, the worst polemics in these pages. It can produce worthless rants. But you will understand the __more focused anger you read, if you can feel the tension that comes with needing to make a case, and knowing that the people around you probably won’t listen.

Of the many stories about Terence Kilmartin that lie in the “too good to check” category, the best concern his ferocious drinking. The Observer’s great literary editor from the 1950s to 1980s and his admirers edited the books pages from Soho pubs rather than anywhere as unconducive to art as the office. One day, a hanger-on told Kilmartin he was getting married. “The thing is,” he continued, “when I’m married, I will have to stop drinking.” Anxious to avoid the impression his fiancee had bullied him, he insisted it was his decision, not hers. “She hasn’t made me,” he said. “The thing is, Terry, I just don’t enjoy it anymore.”

Kilmartin fixed him with a ravaged face and haunted eyes, and boomed: “Do you think that any of us do this because we enjoy it?”

The same applies to the best polemicists. Recognition, when and if it comes, is welcome. You will never be rich, but the pay is all right. Status and money are not at issue, however.

You only write well if you have something to say. You only say it well when you are not intimidated. Intimidation can come in many guises, from the state, the libel law, and the unexpressed prejudices of your time. But the most pervasive is the social pressure to conform with “your side” or “your type of people”. At the Observer, the pressure is less severe than at ideological newspapers, which follow a party line. The relief of working here is that the Observer frees its writers. You can take on unpopular causes, and express unpopular opinions. There is no finer feeling than when an argument you have fought for wins through. But you must savour your victories on the rare occasions you achieve them, and accept that, for most of the time, you will be straining to make a case to a world that is not predisposed to listen.

You cannot and should not enjoy that. If you are enjoying it, you are not trying hard enough.