More than 25 years ago Janet Malcolm outraged journalists by suggesting that they were engaged in a “morally indefensible” trade.

They preyed on their sources, she wrote. Having gained their confidence they went on to betray them “without remorse” and then justified having done so by claiming to have acted in the wider public interest.

Her book, The Journalist and the Murderer, gradually gained a measure of acceptance and her thesis features in many courses about journalistic ethics.

I found myself mentioning it during a discussion on BBC Radio Scotland today about the media revelations of child abuse by football coaches. The question posed by the presenter, Kaye Adams, was whether the coverage had been sensationalist.

Accusations of sensationalism (a supposedly bad thing) are knee-jerk stuff and are a regular topic on radio phone-ins. So I usually pass when asked to speak because I hear myself saying the same thing time after time. There is no winning. We, the mainstream media, are routinely damned if we do and damned if we don’t.

I note, of course, the irony of such programmes being part of the very media brouhaha that they affect to discuss “impartially.”

But I decided to take part this time because I wanted to hear what possible criticisms there might be about the coverage. I couldn’t see how a story of such significance, which had remained hidden for so long and was, in at least two instances, subject to a cover-up, had been sensationalised.

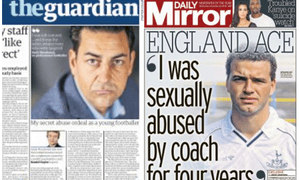

To recap, the story was broken by the Guardian on 16 November when Andy Woodward, a former Bury and Sheffield United player, told how he was sexually abused by a former football coach while at Crewe Alexandra between the ages of 11 and 15.

By any standards, this was a shocking and, yes, a sensational story. Unsurprisingly, it was followed up by other newspapers, on TV and radio, and there was plenty of mentions on social media too.

Six days’ later, another Crewe player, Steve Walters, spoke to the Guardian and made similar allegations. And the following day, a former England and Tottenham footballer, Paul Stewart, told the Daily Mirror he had been sexually abused as a youth player.

In the subsequent days and weeks, there were __more revelations. Two players spoke on BBC TV’s Victoria Derbyshire programme about being abused. The Football Association launched an inquiry.

By 1 December, according to a Daily Telegraph article which cited the National Police Chiefs’ Council, 350 victims had come forward to report child sexual abuse within football clubs.

And the latest twist in the story, reported on the Guardian’s front page today, was the suspension by the FA of Dario Gradi, Crewe’s director of football, pending a top-level investigation.

Having looked back over the national press coverage I cannot detect that it was unduly sensationalised. Nor, indeed, could the other three people on the programme, all of whom deal with child abuse survivors.

In spite of Kaye Adams clearly prompting them to complain, they were not tempted to do so. It transpired that they were not upset by the coverage. Indeed, two of them saw it in largely positive terms.

The third spokesman - Paul Roffey, director of RWA child protection services - did point to the central dilemma: publicity is important in order to advance investigations because people come forward, but it also has the effect of creating anxiety for those suddenly cast into the media spotlight.

My concern, he said, is that “journalism doesn’t understand that tension. We don’t know what the impact is on someone seeing themselves spread across the news.

“It is done for good reasons... but there should be a level of discretion and caution.”

Roffey’s point about the personal effect on someone who “goes public” is one that too few journalists think about: the consequences on the individual (hence my reference to Janet Malcolm’s book).

We all tend to cite “the public’s right to know” as a mantra, implying that the individual’s suffering is for the greater good. Only on those occasions when journalists themselves become the story do they realise just how tough it is to be the central figure in a national story.

Although we are not nearly as cavalier as many critics suggest (and the largely sensitive coverage of football child abuse is a case in point), we cannot deny that a trade based on the disclosure of secrets does have a downside.