The journalist AA Gill, who has died aged 62, less than a month after revealing he was seriously ill with cancer in his newspaper column, once shot a baboon during a Tanzanian safari. He described the killing in the Sunday Times in 2009. “I took him just below the armpit. He slumped and slid sideways. I’m told they can be tricky to shoot: they run up trees, hang on for grim life. They die hard, baboons. But not this one. A soft-nosed .357 blew his lungs out.”

Gill shot the animal, he wrote, “to get a sense of what it might be like to kill someone, a stranger. You see it in all those films: guns and bodies, barely a close-up of reflection or doubt. What does it really feel like to shoot someone, or someone’s close relative?”

The killing, and the way he wrote about it, prompted outrage from animal rights groups. He was unrepentant: “I know perfectly well there is absolutely no excuse for this,” he wrote. “There is no mitigation. Baboon isn’t good to eat, unless you’re a leopard. The feeble argument of culling and control is much the same as for foxes: a veil for naughty fun.”

Gill’s professional life was seemingly devoted to courting controversy as restaurant critic, travel writer and TV reviewer. In 2010, the Sunday Times disclosed he had been the subject of 62 complaints to the Press Complaints Commission in the previous five years, none of them upheld. In the same year, though, the press watchdog upheld a complaint against him made by Clare Balding. He called the TV presenter a “dyke on a bike” in a television review of her BBC4 programme Britain by Bike and compounded the hurt with a mock apology for previously saying that she looked “like a big lesbian”.

In 1998, he was reported to the Commission for Racial Equality for describing the Welsh as “loquacious, dissemblers, immoral liars, stunted, bigoted, dark, ugly, pugnacious little trolls” in the Sunday Times.

In 2006, during a review of a restaurant in Douglas, he described the Isle of Man as a place that had “fallen off the back of the history lorry to lie amnesiac in the road to progress … everyone you actually see is Benny from Crossroads or Benny in drag … The weather’s foul, the food’s medieval, it’s covered in suicidal motorists and folk who believe in fairies.” A local politician called the review an “unacceptable and scurrilous attack”. In another article, Cleethorpes came in Gill’s crosshairs, inspiring the local police commissioner to describe Gill, not inaccurately, as “a tweed-suited, Mayfair-based writer whose only experience of the north of England was his visit to Cleethorpes and his regular trips salmon fishing in Scotland”.

If contempt and hatred were virtues, Gill was the most virtuous of men. “Hate is good,” the self-professed Christian wrote once. “Hate is fine.” In a 2012 review of Mary Beard’s TV documentary Meet the Romans, Gill wrote that the Cambridge professor “should be kept away from cameras altogether”, prompting Beard to retort that he was afraid of smart women. He described actor Maureen Lipman as “lemon juice in the eye, she is chewing silver paper, she is a three-flush floater, sand in your socks and one blocked nostril”. In 2014, he won Hatchet Job of the Year for his review of the ex-Smiths singer Morrissey’s autobiography, which he described as “a cacophony of jangling, misheard and misused words … a sea of Stygian self-justification and stilted self-conscious prose”.

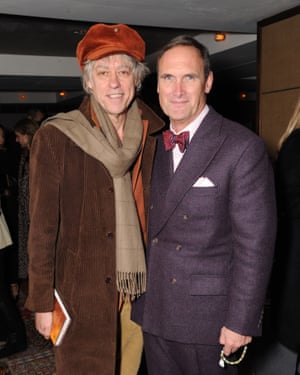

Many, though, admired his writing, among them his fellow journalist Lynn Barber, who wrote: “Gill is a wit and a charmer. Even when he’s wrong, he’s superbly full of himself.”

To be fair, he did have some good lines. He once critiqued Starbucks’ business model: “Asking Americans to make coffee is like asking them to draw a map of the world”. He denounced gastropubs: “Food and pubs go together like frogs and lawnmowers”. He skewered England’s heritage industry in a TV review: “Beautifully shot, impeccably paced, it was a clear, unrelenting look at the National Trust, its friends and enemies, and it makes you want to burn your passport and beg the Luftwaffe to have another go.”

He defended TV, and not just because writing about it helped pay his mortgage: “The only people who ever thought television rotted the brain and made kids dumb were those with a vested interest in other ways of learning, or those who were intellectually insecure, usually about books”. For such bons mots, he was regularly given press awards.

Gill was born in Edinburgh, but the family moved south when he was one. His father, Michael Gill, was an award-winning director of films for television, including Kenneth Clark’s 1969 series Civilisation. His mother, Yvonne Gilan, was an actor who later taught public speaking to businesspeople. Gilan had appeared as Mme Peignoir in an episode of Fawlty Towers when Gill was a teenager. “When my mum was asked to do it, she showed me the script and I said, ‘This is terrible!’ That was my first piece of criticism.”

From an early age, Gill suffered from a stammer and dyslexia. He was sent to a progressive boarding school, St Christopher’s in Letchworth. He reportedly detested the place, not least because the food was vegetarian. Indeed, his long-running animus in restaurant reviews against vegetarians (“people who get pleasure from not eating things”) may well be explained by this childhood trauma.

He was, perhaps unsurprisingly, an opinionated boy and had a testy relationship with his father. “I was a militant teenager and he felt infuriated and threatened and I felt put upon and hard done by,” Gill recalled. “And at one point I remember him saying, ‘You should be a journalist’ – he’d started as a journalist – and my being furious and saying, ‘But I can’t read or write!’ That was years and years before I ever thought of writing.”

Gill had another vocation. He had wanted to be an artist from the age of five. So, after leaving school aged 19, he studied at the Slade School of Art in London. After art school, he spent seven years trying unsuccessfully to be an artist. “I was just good enough to keep myself doing it, but not good enough to be top-rate. And that’s really horrible. I tried lots of things – portrait painting, murals, illustration – and I could just about make a living but it really wasn’t going anywhere.”

Gill started drinking at the age of 15 and by his early 20s was consuming a bottle of Scotch a day. On the dole through much of his 20s, he reckoned to spend £40 a week on alcohol even though his income was £19. “I suppose I was endlessly borrowing money off people. And I always had very accommodating girlfriends.” During this time, he was briefly married to the writer and journalist Cressida Connolly.

In his 2015 memoir Pour Me: a Life, Gill described the alarming symptoms of his alcoholism: “Death signals from the blood in the bog, the pus in the sock, the tingling in the fingers.” In an interview, he recalled other symptoms: “I had DTs, both the delirium – seeing things, seeing monsters – and the tremens, uncontrollable shakes. I had peripheral neuritis which is tingling in your face and fingers, like palsy, and the worst thing was alcoholic gastritis which means feeling sick whenever you eat and throwing up every single morning, and you then start damaging your oesophagus. I also burst all the blood vessels in my eyes. I’m still covered in scars that I don’t know how I got.

“Ultimately what is the real destroying thing is the depression, the self-loathing, and the fear – a lot of being drunk is to do with being frightened all the time.”

When he was 30, he was told his alcoholism would kill him. So, on April Fool’s Day 1984, he checked into Clouds House addiction treatment centre in Wiltshire after sharing two bottles of vintage champagne with his father on the train. With the help of an Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor he “12-stepped” his way to recovery and, in gratitude, renamed himself “AA” Gill.

In 1991, Gill married the venture capitalist Amber Rudd, who was elected Conservative MP for Hastings and Rye in 2010 and is now home secretary. Their marriage lasted five years, during which time the couple had two children, Flora and Alasdair. He was still trying to paint. But he was also teaching cookery courses, having taught himself how to cook as an art student.

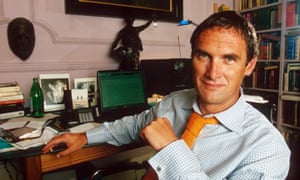

Then a friend asked him to write a 600-word piece on the artist Craigie Aitchison, and other art reviews followed. It was a “Damascene moment”, he said, perhaps showing that his father’s careers advice was right. “When I started to write, it really was like coming home. I had that feeling of, ‘Oh for God’s sake, this is what I was supposed to be doing’. And so the pleasure is in finding something you’re good at.”

That said, there was a problem: his dyslexia. Throughout his journalistic career, he was obliged to dictate his columns because his writing was indecipherable to anyone but him.

His break in journalism came in 1991 when Jane Procter, then editor of Tatler, asked him to write about his detox experiences. She was so impressed by his article, which was published under a pseudonym, that she hired him to write a cookery column. Two years later he was poached by the Sunday Times as the paper’s TV and restaurant critic and as a feature writer. He also worked as columnist for Esquire magazine and wrote about fatherhood for GQ.

In 1995, he left Rudd for South African model Nicola Formby, a writer and editor at Tatler and, latterly, a food consultant. According to Lynn Barber, Gill wrote “many nauseating articles about her devastating beauty”, referring to her in print as “the Blonde”. In 2007, Gill and Formby had twins, Isaac and Edith.

In 1999, his younger brother, Nick, told Gill: “I’m having a miserable time. I’m going to disappear for a bit”. Nick Gill had been one of the first English chefs to win a Michelin star, working at a country-house hotel called Hambleton Hall, but his own restaurant had not been a success. He has not been seen since. “Can I forget about him? No,” Gill told an interviewer. “I feel sad for my mum, I feel sad that my dad died not knowing where his son is. I’m sad for Nick’s kids. And I’m sad for Nick.” A 1979 painting by Gill of Nick was auctioned at Christie’s in 2015. “I don’t know where it came from,” Gill said later. “I didn’t pursue it. If Nick wanted to get in touch with me, I’m not hard to find.”

Until the end AA Gill remained a prolific journalist. Just three weeks before he died, he began his Sunday Times newspaper column by bluntly informing his readers that he was suffering “an embarrassment of cancer”, adding: “There is barely a morsel of offal that is not included. I have a trucker’s gut-buster, gimpy, malevolent, meaty, malignancy”. In an interview for the paper the same day, he said he regarded himself as having been lucky to have lived so long.

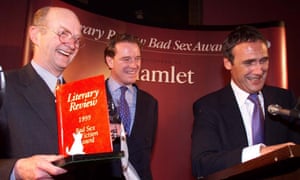

He managed to find the time, too, to publish books, including two novels, Sap Rising (1996) and Starcrossed (1999). His travel writing was collected as AA Gill is Away (2002) and AA Gill is Further Away (2011). His TV columns were collected as Paper View (2008) and the best of his Tatler and Sunday Times food writing as Table Talk (2007).

Among his pleasures away from writing was cooking, which he said was therapeutic, or, as he put it, “four and 20 black thoughts baked in a pie”.

“I’m not a contrarian,” Gill told an interviewer. “I do bristle when people accuse me of that. I’ve never had to make up an opinion and I’ve never had to up the volume. I think by nature I’m probably someone who was born pointing up the down escalator.”

He is survived by Nicola, his four children, Flora, Alasdair, Edith and Isaac, and his mother.

• Adrian Anthony Gill, journalist, born 28 June 1954; died 10 December 2016.