Journalism, so the old adage goes, is the first draft of history. But some journalists don’t just report on historic events, they end up shaping them, for good or ill. A dispatch from a war zone can alert the world to the need for action; a scoop highlighting systemic failures in a public institution can trigger calls for change; a waspish epithet judiciously bestowed on an unfortunate politician by an influential commentator can have career-changing consequences for the individual concerned.

This is, for want of a better phrase, “rock-star journalism”, the stuff any hack – including this one, who has spent two decades at the Observer – dreams of. But while we may like to think that the cult of the individual is a particularly modern invention in British journalism, the life and times of Observer journalist Vincent Dowling, who was earning his living in Fleet Street in the first half of the 19th century, explodes that myth.

The epithet “Fleet Street legend” hardly seems to do Dowling justice. His life was the stuff of novels – part Boy’s Own adventure, part Ian Fleming – though today his role in historic events hardly merits an entry in Wikipedia or the various histories of journalism, perhaps because he cut an ambiguous figure even in his own lifetime.

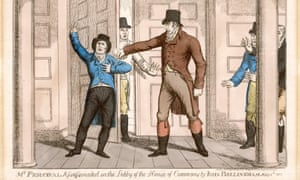

If Dowling is known at all today it is for being present in the lobby of the House of Commons when John Bellingham shot the prime minister, Spencer Perceval, on 11 May 1812.

In fact it was the 27-year-old Dowling who removed the loaded pistol from Bellingham, a man with whom he had spoken several times in the parliamentary gallery and who had asked Dowling’s help in identifying members of the cabinet. Other journalists were present in the immediate aftermath of the shooting, but Dowling knew a scoop when he saw one and his first-hand account was a massive coup that helped catapult his career into the stratosphere.

Having witnessed Perceval’s assassination may have had a bearing on Dowling’s inclinations after the Observer was bought by William Clement in 1814. Clement, like his predecessor, WS Bourne, accepted a Home Office subsidy in return for allowing the government to help mould the paper’s political opinions, and in Dowling he found a sympathetic lieutenant.

Dowling became a Home Office informer, paid to provide evidence against a group of men known as the Spencean Philanthropists, who were demanding parliamentary reform and were seen in some quarters as dangerously revolutionary. Dowling used his shorthand skills to keep contemporaneous notes of what was said at their meetings, evidence that was later used in court against the men.

But the men were acquitted, partly due to concerns over the reliability of Dowling’s evidence. One of the accused, Henry “Orator” Hunt, who went on to become a key figure in the formation of the Chartist movement, was so outraged by Dowling’s spying that he accosted him in Fleet Street with a horsewhip.

It would be wrong to view Dowling simply as an establishment stooge, however. He famously won the trust of Queen Caroline, the estranged and scandalous wife of George IV, who had tried to divorce her on the grounds of adultery. Following her husband’s accession to the throne in 1820, Caroline decided to return from abroad to assert her position as queen, a project that incensed the court but enjoyed popular support.

Putting his own life at risk, Dowling crossed the Channel on a stormy night in an open boat, in order to be the first back to London with the news of Caroline’s return. Sympathetic coverage of Caroline’s plight in the Observer helped further her popularity with the London crowd, and was an early example of this paper’s critical attitude towards the royal family.

In later years, Dowling turned his attention to boxing, launching a series of campaigns against corruption in sport. It’s a shame he’s not around now: there’s plenty of material for him to get his teeth into.