Two years ago, when the UK had a future in the European Union and Ed Miliband was a potential prime minister, the chief business commentator of the Financial Times, John Gapper, announced the demise of Britain’s rightwing tabloids. Unusually for an FT journalist, Gapper had once worked at the Daily Mail, and at the FT he often writes about the media, sweepingly and authoritatively even by that paper’s standards. “The era of the Fleet Street tabloids, the populist and fearsome emblems of British culture and politics, is over,” he wrote on 25 June 2014. “It has been over for some years, in fact, but neither they nor their critics chose to admit it.”

He pointed to their shrunken print circulations: in 1950 the Daily Express was “the world’s best-selling paper”, he wrote, and “sold __more than 4m copies each day”. Yet by 2014 it was selling barely a ninth of that; and it has weakened further since. “The tabloids appeal to a readership limited by class, occupation, and social attitude,” Gapper continued. “That is not sufficient in the digital era. Young people are not loyal to one tabloid title and few of them will subscribe online.”

Gapper cited the phone-hacking scandal which closed the News of the World in 2011; competition from politically neutral, free tabloids such as Metro; the distraction of readers by smartphones; and the advancing years of key tabloid figures such as Paul Dacre, now 67, who has been the crusading, splenetic editor of the Mail for almost a quarter of a century. Gapper predicted that Dacre would probably be the last tabloid editor to successfully “express their readers’ inner thoughts and emotions … __more strongly than the readers could themselves”.

In recent years, the many observers and enemies of the tabloids have repeatedly forecast their political decline. In 2010, the blogger Sunny Hundal wrote in the New Statesman that that year’s general election had been “notable for how little impact the tabloids had”. He concluded, “It’s highly unlikely the Sun can claim victory after an election ever again.” This June, in the middle of the EU referendum campaign, the i newspaper declared on its front page, “The Media Won’t Decide This Vote”. In August, a former managing editor of the Sun, Stig Abell, wrote in the New York Times that the other tabloids had become “living relics”, with the Express “no more than an incontinent shriek of made-up facts about health and immigration”. The headline for the piece was “Britain’s Paper Tigers”.

Yet on 23 June 2016, almost two years to the day after Gapper had written their obituary, one of the biggest, oldest dreams of the tabloids came spectacularly to life, when Britain voted to leave the EU, against the predictions of most broadsheet commentators. It was an outcome for which the tabloids had campaigned doggedly for decades, but never more intensely – or with less factual scrupulousness – than this spring and summer, when the front pages of the Sun, Mail and Express bellowed for Brexit, talking up Britain’s prospects afterwards, in deafening unison, day after day. Two days before the referendum, the Sun gave over its first 10 pages to pro-Brexit coverage.

The referendum has not been the only tabloid triumph of the last 18 months. At the 2015 general election, again contrary to most predictions, the Conservatives won a majority against the Labour bogeyman the papers had alternately mocked and feared for the previous five years: “Red” or “Weird” Ed Miliband. At Loughborough University, Prof David Deacon and his colleagues have studied the tabloid coverage of the last six general elections, going back to 1992. “We were doing our initial analysis of 2015 while the campaign was going on,” he remembers, “and there seemed to be laughably extreme anti-Labour headlines. The levels of partisanship were at least the equal of what we recorded in 1992,” widely considered the previous high point – or low point – of tabloid electoral influence.

“On polling day in 2015,” Deacon continues, “I was doing the final data runs, and I thought to myself, ‘If Miliband gets a hung parliament, in spite of this hostility, it will be extraordinary. This election will put us out of business.’” He pauses. “But it didn’t.”

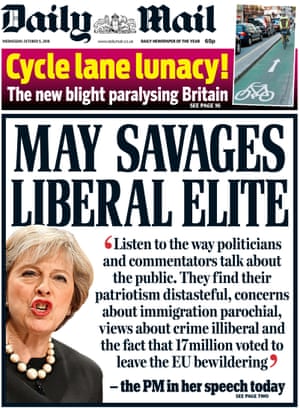

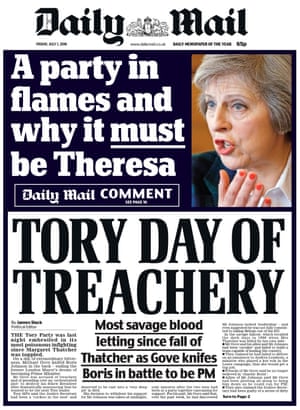

Finally, this July, Theresa May suddenly swept past the favourite Boris Johnson to become Conservative leader and unelected prime minister. The Mail has long admired and promoted her as a stern, controlling figure, like Dacre himself. To his usually formal paper, which was thrilled by her fierce party conference speech this month, she is “Theresa”.

British politics now feels relentlessly tabloid-dominated. From the daily obsession with immigrants to the rubbishing of human rights lawyers, from the march towards a “hard Brexit” to the smearing of liberal Britons as bad losers and elitists, the tabloids and the Conservative right are collaborating with a closeness and a swagger not seen since at least the early 90s.

“The Sun and Mail have more power now than they have for a long time,” says David Yelland, editor of the Sun from 1998 to 2003. “You could argue that in Brexit the tabloids had their most powerful moment ever.” In a text less than an hour after the Brexit victory was declared, the current editor of the Sun, Tony Gallagher, told the Guardian’s media editor: “So much for the waning power of the print media.”

Even the most confident and successful modern British politicians have regarded the tabloids as culturally and electorally pivotal. In 2012, Tony Blair told the Leveson inquiry into the behaviour of the British press: “If you have a readership of three to four million … that’s power … I don’t know any other way of describing it.” In his autobiography, Blair writes of his decision as Labour leader to appease the Sun and its proprietor Rupert Murdoch: “Not to [do so] was to say carry on and do your worst, and we knew their worst was very bad indeed.”

Like almost every book about New Labour, Blair’s has dozens of index entries for the Sun and Mail. Conservatives tend to be more reticent about their relations with the tabloids: there are no index references to the Sun in either volume of Margaret Thatcher’s memoirs. But shortly before her 1987 general election victory, she spoke privately about Murdoch to her confidant Woodrow Wyatt. “We depend on him to fight for us,” she said. “The Sun is marvellous.”

According to research by YouGov, the paper you read is still “a far better predictor of Labour and Tory support than any other indicator”. This applies to all national papers – in 2015, Guardian readers chose Labour over the Tories by 10 to one. But with the rightwing tabloids, uniquely, the link is rapidly growing stronger. At the 2015 general election, the Tory advantage over Labour among Sun readers was one-and-a-half times as big as it had been in 2010. Moreover, as John Curtice of Strathclyde University, the veteran analyst of British voting behaviour, points out: “People who still read papers in print are disproportionately politically interested. They vote!”

The word “tabloid” was invented in 1884 by the pharmaceutical magnate Henry Wellcome; before it referred to pithy newspapers, it meant a concentrated dose of medicine.

Consider some headlines from the Express this autumn: “Migrant Influx Is Threatening To Destroy Our Way Of Life”; “Muslim Bus Driver ‘Put Children’s Lives At Risk’ By Stopping For Prayer”; “Benefit Cheats Spared Jail As Fraud Rockets”. For the rightwing tabloids, they are unremarkable – such themes and stereotypes and phrases have run through the papers for decades: on front pages, in news stories, in features, editorials and pieces by columnists, almost all the articles agreeing with each other, almost every day. The papers have tirelessly devoted themselves to what the Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci referred to as the manufacturing of “common sense”, by which he meant the partisan but often unnoticed and unchallenged assumptions that tilt public opinion rightwards. In 2013, an in-depth survey by Ipsos MORI revealed that Britons vastly overestimate the number of British immigrants, Muslims and benefit fraudsters.

In an era when agreed facts are becoming rarer, and voters are increasingly impatient and distracted, but also disorientated by shock events, influencing how issues are talked about is more important than ever – possibly more important, in fact, than influencing elections. In Britain, uniquely among democracies, a few tabloid newspapers are at the heart of both; their preoccupations so familiar that the terms “tabloid” and “rightwing tabloid” have become almost synonymous.

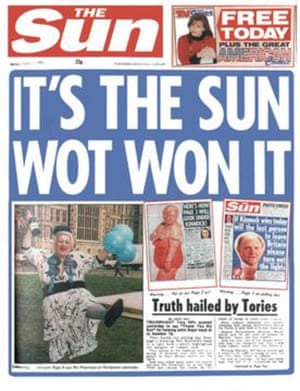

Yet the exact workings and nature of their influence are fiercely disputed. Politicians, journalists, academics, and tabloid proprietors say contradictory things about it. Defenders of the papers say that tabloids understand and represent their readers; critics say that they talk down to them and manipulate them. Even the owners of tabloids can’t always keep their story straight. In 2012, Murdoch told the Leveson inquiry that the Sun’s famous claim after the 1992 election – “It’s The Sun Wot Won it” – had been “tasteless and wrong … We don’t have that sort of power.” But at the Sun’s offices in London, some of the rooms have glass walls with reproductions of its most mythologised headlines embedded in them, including the front page from the day of the 1992 election, about the then Labour leader, Neil Kinnock: “If Kinnock wins today will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights.”

Like Miliband, Kinnock unexpectedly lost. Murdoch told the Leveson inquiry he thought this front page was “absolutely brilliant”. He could not resist revelling in his paper’s power, it seemed, even as he denied it.

In 1992, the political scientist Ken Newton wrote that identifying the political role of newspapers was “a classic conundrum of the behavioural sciences”. Do people think and vote as rightwingers because they read rightwing papers – or is it the other way around? Are tabloids just one voice in a larger media babble, or do they play a unique role in setting the agenda for other journalists, such as broadcasters? To what extent do the tabloids shape their readers’ social values – or have the tabloids’ own values been made to shift by changing public attitudes towards race and gender and sexuality?

In the Britain of Theresa’s Brexit and seemingly perpetual Tory government, the rightwing tabloids reign again – even as their business, like the rest of the print media, continues to crumble. Is theirs a brittle supremacy? Or is their hold on the national discourse secure for another generation?

One way to investigate these questions is to tell the story of their political influence on modern Britain. It is not a simple tabloid tale.

Britain is in many ways a perfect environment for a partisan press. It is a small, centralised country with a raucous party politics and an enduring culture of national newspapers. Unlike local papers, the nationals do not have to appeal to everyone, but can have intense relationships with particular readerships. British newspapers first appeared regularly during the civil war of the 1640s: the earnest Mercurius Britannicus supported parliament, the mocking Mercurius Aulicus backed the royalists. Three hundred years on, political bias remained so blatant that in 1947 Clement Attlee’s Labour government established a royal commission to investigate the press, in particular the power of its disproportionate number of rightwing proprietors. Lord Beaverbrook, the domineering owner of the Express, told the ineffectual commission: “My purpose originally was to set up a propaganda paper, and I have never departed from that.”

Two years later, the pioneering social research organisation Mass Observation conducted one of the first British studies of the interactions between newspapers and their readers, by scrutinising press consumption in libraries and other public places. “Most people choose their paper primarily for its politics,” it found. Fifty-eight per cent of people read political news stories, far more than read sport or “gossip”. With huge electoral turnouts and party memberships, Attlee’s Britain was a highly politicised society. “Newspaper influence on [reader] opinion,” the study went on, was “a subtle, almost imperceptible process”: either “the long-term reinforcement of opinions already held”, or to “sow seeds and implant suggestions on points to which people have up to now given next to no thought”.

But Mass Observation warned over‑ideological proprietors: “People tend to resist newspaper influences that lead them in a direction they are not disposed to follow.” During the 1945 general election, one Express headline read, “Gestapo In Britain if Socialists Win”. Attlee won by a landslide.

So used to thinking of tabloids as always omnipotent, modern Britain has forgotten that their political influence actually dwindled during the postwar decades. Improving literacy and the complexities of the war reduced the impact of simplistic newspapers. Mass Observation found the press falling behind “books”, “personal experience”, and “friends and family” as political influences. The arrival of television during the 50s, which was not allowed to be partisan, made the Mail and the Express, founded in 1896 and 1900 respectively, look still more like bombastic Victorian throwbacks. So did the increasingly consensual nature of postwar party politics.

In 1952, the Labour politician and diarist Richard Crossman spent a hospital stay reading a British newspaper history: “What struck me,” he wrote afterwards, “was the enormous power of the press in politics before 1918 and its steady decline since... Today, [when there is] a campaign against a cabinet minister, the effect is usually to strengthen his position.”

As the economy recovered from the war, advertising revenue became more important to papers, and this brought a pressure to publish fewer political, potentially reader-alienating stories. According to the media historians James Curran and Jean Seaton, the amount of “public affairs” coverage in the tabloids halved between 1945 and 1975. The Mail and Express carried on backing the Conservatives, but their readers increasingly ignored the editorials: by 1963, 28% of Mail readers and 38% of Express readers supported Labour.

In 1964, the struggling Daily Herald, founded half a century earlier as a radical paper for striking trade unionists, was relaunched as the Sun. It remained Labour-supporting; but as its apolitical-sounding, blandly uplifting name might suggest, it was more interested in consumerism, and in what it called “pacesetters”: young working-class people, often women, who were joining the expanding middle class of southern England.

The idea that newspapers should no longer lecture their readers received support from academia. The Sun was conceived partly on the advice of a sociologist and social forecaster, Dr Mark Abrams. He produced reports with graphs and tables which appeared to prove the existence of a new, increasingly well-educated, less politically tribal, mass newspaper readership. Meanwhile in America, where most academic work on the media was done, the analysis of press influence converged on a “minimal effects model”. It noted that few voters changed their minds during presidential races, when coverage of politics was at its most feverish, and concluded that papers were not much of a factor in electoral contests.

Like many postwar American ideas, “minimal effects” quickly crossed the Atlantic, and helped shape the thinking of the small number of British media analysts. In 1974, the respected Colin Seymour-Ure wrote languidly in his book The Political Impact of Mass Media: “Most British national newspapers ... are ‘partisan’ in only a loose sense.” Beaverbrook had died in 1964. The equally rightwing co-creators of the Mail, Viscount Northcliffe and Viscount Rothermere, had died in 1922 and 1940, respectively. Newspapers were increasingly controlled by corporations seeking profits or prestige rather than political clout. In a 1977 essay titled “The Organization of Public Opinion”, the media academic Tom Burns concluded: “The power of the press barons has gone.”

It had not. In 1969 Murdoch bought his first British paper, the News of the World. While mostly interested in sex and scandals, it was traditionally a Tory paper. According to Roy Greenslade’s reliable 2003 book Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits from Propaganda, Murdoch was permitted to acquire it partly because the other potential buyer was Robert Maxwell, then a book publisher and Labour MP.

Murdoch’s own politics, at this stage, were a slightly unformed but usefully ambiguous mix, both pro-business and pro-trade union. Despite the elite-bashing persona which he would deploy, brilliantly and shamelessly, in the intensely class-sensitive world of British newspapers for decades to come, he was in fact the son of an Australian press magnate, Sir Keith Murdoch. Sir Keith had been so influenced by the Mail’s Northcliffe that he was nicknamed Lord Southcliffe. When Murdoch junior was asked if he would tell the News of the World what to say, he replied: “I did not come all this way not to interfere.”

When the Sun was also put up for sale in 1969, after its first incarnation attracted too few readers, Murdoch and Maxwell again competed to buy it. Maxwell wanted to slim the Sun’s staff, while Murdoch assured the paper’s powerful unions that he had no such intentions. Again, Murdoch won. His Sun tried to be youthfully, fashionably left-liberal: it was against the death penalty, nuclear weapons and the Vietnam war; for Labour and personal freedom. Its endorsement of the party at the 1970 general election deferred to readers rather than tried to browbeat them: “This … far-from-perfect Labour government has just about earned the right to … another term of office. That is our view. But you have a mind of your own.”

During the late 60s and early 70s, the large advantage that the Conservatives had always enjoyed among the tabloids, in terms of both circulation and opinions expressed, suddenly evaporated. When the national union of mineworkers (NUM) went on strike in 1972 against Edward Heath’s Tory government, the Express, despite still being owned by the Beaverbrook family, was sympathetic: “These men do a hard, dirty, dangerous job … All they ask is a decent wage. They should have it.” The Mail acknowledged “widespread public support” for the strike, and commented: “Sympathy for the miners is a good cause. It makes sense for Britain.” The editor of the Sun, Larry Lamb, was the son of an NUM official and had once edited a union journal. Of the Sun’s pro-strike coverage, Murdoch said afterwards, “We certainly pushed public opinion very hard behind the miners.”

Just as startling and forgotten, in Britain’s first referendum on EU membership, in 1975, the tabloids urged their readers to vote in favour of Europe. When the pro-EU side won by 67% to 33%, the Mail rejoiced: “This is the most crushing victory in British political history. The effects of this thunderous YES will echo down the years.”

Yet the tabloids’ flirtation with cosmopolitanism and the left was short. In 1974, the miners went on strike against Heath again, and the Mail condemned them. When he called a general election that February, to try to end the dispute, the Sun endorsed the Conservatives. Some of this shift was a reaction against the increasing radicalism of parts of the union movement and the Labour party. The Mail became preoccupied by the presence of communists in the NUM. But the tabloids were also increasingly hit by strikes themselves. The stalling, inflationary British economy of the mid-70s had brought lower advertising revenues, higher newsprint costs, and higher wage demands. All Fleet Street papers had prickly unions, but the Sun’s were the most rebellious of all, regularly stopping editions from appearing.

James Alan Anslow joined the Sun in 1977, and worked there on and off for four decades, as well as writing and lecturing in academia about tabloids and their readers. “Soon after I started at the Sun,” he told me, “I was working on production, and I let the word ‘victory’ through on a headline about a strike by the firemen’s union. Kelvin MacKenzie [who later became the paper’s most aggressively rightwing editor] gave me a bollocking. He said, ‘Don’t you know what we’re all about?’”

After Margaret Thatcher seized the Tory leadership from Heath in 1975, Larry Lamb quickly became a convert. The Sun editor would invite her to his office for evening chats and whisky, and published so many favourable pieces about her that the more cautious Murdoch, anxious about the Sun’s large residue of Labour readers, would phone Lamb and ask, “Are you still pushing that bloody woman?” The Sun had backed the losing side at both the 1970 and February 1974 general elections. But by the late 70s many voters were turning against unions and collectivism, and the individualistic Sun’s circulation surged, doubling over the decade. In 1978, it overtook its once-dominant leftwing rival, the Daily Mirror, to become Britain’s best-selling daily paper. In January 1979, amid the strike chaos of the Winter of Discontent, the Sun lethally punctured the credibility of the Labour prime minister, Jim Callaghan, with a headline that sounded like a quote from him but was actually disguised editorialising: “Crisis, What Crisis?”

The Mail was an early and effective Thatcher ally too. Its editor during the 70s and 80s was David English, a zealously rightwing former entrepreneur who had backed her coup against Heath (the Mail was the only paper to do so). English modernised the Mail’s design, and turned the paper into a less fusty, more seductive advocate of Conservative values, presenting them as basic British common sense, somehow above mere party politics. The day before the 1979 general election, the Mail’s front page read, “The Woman Who Can Save Britain”. The Sun’s endorsement of the Conservatives was less personal and more equivocal, but eye-catching: “VOTE TORY THIS TIME.” The return of the rightwing tabloids was complete – and with it came the press culture we still live in now.

As British voters have become more disengaged since the 70s, the tabloids’ political messages have had to become louder. “VOTE FOR MAGGIE,” yelled the Sun’s front page on the day of the 1983 general election. When Labour moved rightwards after losing, choosing the pragmatic Kinnock as leader, the Sun immediately dismissed him regardless: “He has no intellectual depth, no coherent philosophy.”

Kinnock’s strategist Philip Gould, who would become Labour’s key interpreter of voter behaviour during the 90s, began reading the tabloids closely. “I looked at those papers and silently wept,” he wrote after the 1992 general election campaign. Some tabloid journalists had mixed feelings about their papers’ power. James Alan Anslow remembers: “When the Sun did the lightbulb” – its famous 1992 front page of Kinnock’s balding head inside a bulb – “I was out on the doorstep canvassing for him. Politically, I thought it was awful. Journalistically, I felt … professional admiration. I couldn’t help smiling. In the office after the paper came out, there was a lot of chatting and smiling. There was a sense of being in amongst it – of counting.”

When Labour lost, despite a tired Conservative government, there was a surge of academic and media interest in the tabloids’ political role. The “minimal effects” model had already begun to attract British doubters. In 1991, the media analyst William Miller had written about what he instead called “the Basildon effect”. In this heavily working-class Essex constituency, which had one of the highest proportions of Sun readers in the country, a small and supposedly vulnerable Conservative majority had risen rather than fallen at the 1987 election. According to Miller, this swing had happened late in the campaign – when the Sun’s onslaught on Labour was at its loudest – and it had been repeated in other similar Tory marginals. He suggested the paper had played a major role.

In 1992, John Curtice interviewed a panel of voters from across the country, before and after the general election. Unlike Miller, he did not find tabloid readers shifting from Labour to the Conservatives. But he wrote that the papers did play a part in “winning over or maintaining in the Conservative camp electors who might otherwise have abstained or voted Liberal Democrat”. All the scare stories about Labour, it appeared, had persuaded these pivotal voters to choose the Tories as the lesser evil, as they would in 2015.

More ominously still for non-Tories, in 1992 Ken Newton found that people with Labour views who read a rightwing paper – of whom there were still millions – were more likely to vote Conservative than people with Tory views who read a leftwing one were to vote Labour. Tory papers were better at making converts than Labour ones, in other words, just as they would prove better at turning leftwing readers into Brexiters than the Labour press would be at creating remainers.

By the 90s, many political observers assumed that readers of rightwing tabloids were a sort of block vote, to be deployed en masse by proprietors as decisively as union members had been by their leaders during the 70s. In academia and beyond, the tabloid factor was frequently cited as a reason why Labour would never win power again.

There were weaknesses in this argument. The gap between the Conservative share of the newspaper market – between 70 and 80% – and the Conservative share of the vote at general elections – around 40% – suggested that papers were not terribly efficient creators of Tory voters. Even in 1979, when the Sun had said “VOTE TORY”, fewer than half of its readers had done so. Another third actually believed it had endorsed Labour. As Britain became a less deferential, less politicised society, readers could no longer be relied on to absorb or even notice bossy political articles in the way that they had in the editorialists’ heyday of the 40s.

Yet by the mid-90s, after four consecutive general election defeats, Labour was not interested in examining such complexities. Under Blair, the party generally sought to accommodate rather than challenge rightwing interests: Gould decided that the Mail was “the key influencer of Middle Britain”, Blair that Murdoch was “immensely powerful”. More than a year before Blair became Labour leader in 1994, a delicate political dance began between him and the tabloids – each side seeking to draw maximum advantage from the rising strength of the other – which culminated in the Sun endorsing Labour at the 1997 general election.

The day before the announcement, Blair’s press secretary Alastair Campbell was contacted by the Sun and told to call its editor, Stuart Higgins. “He said they were going to come out for us in a big front page tomorrow,” Campbell wrote in his diary, capturing the sense of mutual triumph and machismo. “Stuart said Rupert Murdoch was sure [about Blair], and laughed … I took [Blair] to one side and … I said you remember in 1994 when I said we should try to get the Sun on board and you said you weren’t sure it was possible, well, they are. He thought it was good news in its own right … [and] in the effect it would have on the other side’s morale.” The next day, the Today programme on Radio 4 reported that the Conservatives felt bewildered: “Old friends” – its correspondent meant the Sun – “are passing them by on the other side of the street.”

Less noticed was the fact that the paper had endorsed Labour on its own, almost unchanged, rightwing terms. “Like us, Blair recognises that the Tories under Maggie Thatcher achieved remarkable reforms,” said the Sun. “Blair has promised to slay the dragon of Europe,” it went on, and might even “tame” the welfare state. As well as choosing governments, the tabloids now wanted to decide what they did.

In 2004, George Lakoff, a professor of linguistics at Berkeley, published a deceptively breezy political book called Don’t Think of an Elephant! Its central argument was that how issues are “framed” – which points of view the media and other political tastemakers defined as acceptable, and the language used to do so – largely decides how voters think about them.

For the last two decades, through Labour, coalition and Conservative governments, the tabloids have successfully chosen and then framed most of the debates that have dominated British domestic politics, ensuring that law and order, immigration, the role of the state, and Britain’s relationship with Europe have all been discussed in ever more rightwing terms.

The Blair government’s determination to be “tough on crime”; the Brown government’s “British jobs for British workers”; the Cameron government’s onslaught on benefits-claiming “shirkers”; the May government’s “Brexit means Brexit” – all have been catchphrases, not always with workable policies attached, intended to “please the tabloids”, in the euphemistic stock phrase of British political punditry.

On occasions, the newspapers have directly intervened in the making of government policy. According to Nick Davies’s book Hack Attack: How the Truth Caught Up with Rupert Murdoch, in 2001 the Sun forced Brown as chancellor to permit more private sector involvement in the NHS. First, the paper condemned his cherished plan to increase NHS spending as too profligate, writes Davies, then a “panicked” Brown – desperate not to be portrayed as a traditional tax-and-spend leftwinger – “contacted the Sun … agreed to rearrange his diary so that he could go to their office that day … [and] sat down with the Sun’s outspoken rightwing political editor, Trevor Kavanagh, for an interview which … rapidly became a negotiation about policy.”

In the meantime, policy ideas that have been popular with the public but not with these papers, and their proprietors – raising taxes on the wealthy or on property; renationalising loathed and ineffective privatised utilities – have almost never been enacted.

During the Blair era, tabloid circulations, like those of all newspapers, stagnated and then fell. British party politics, fixated on the “centre ground”, was often as consensual as it had been during the 50s, when the tabloids had felt obliged to tone down their rhetoric. Yet this time they did the opposite, emboldened by the Blair government’s acceptance of their agenda and eagerness to have friendly relations. The tabloids became more influential still.

Meanwhile, as the media in general adjusted to a new world of internet competitors, squeezed budgets, and recycled content, the papers became a dependable source of polemic for other outlets. “Sky and the BBC are still obsessed by reviewing the papers,” says Charlie Beckett, a former TV executive who is professor of media at the London School of Economics. Presenters holding up tomorrow morning’s front pages to the camera, he points out, “is cheap telly”.

The need for broadcasters to be balanced, once seen as a threat, has created a market for tabloid shrillness

Yelland says: “The first thing you do when you’ve put together a front page, is get it over to Sky, to the paper review shows.” Tom Baldwin, Ed Miliband’s press strategist as Labour leader, told me: “They could say ‘Black Is White: Exclusive’ on the front of the Mail, and the next day, there’d be a story on the BBC: ‘Controversy over whether black is white …’” The legal requirement for British broadcasters to be balanced, once considered a threat to the tabloids, has created a new market for their shrillness.

It is even possible that the papers’ political stances are even more influential now than in the past, precisely because they are less and less read. Their positions are simply assumed – rather than widely scrutinised for flaws or contradictions – and politicians and public opinion adjust accordingly. Gramsci, who died in 1937, would be appalled and fascinated.

As the editor of the Sun, says Yelland, “I was very much aware that most people were not reading the political stuff. But the Sun set the mood music of Westminster, of the lobby [journalists], of the morning meetings in every department in Downing Street.” Like any good tabloid journalist, he may be overstating a little, but to manipulate the elite while insisting your journalism is for the masses is certainly quite a trick.

While Labour leader, Miliband tried to break out of his party’s suffocating tabloid relationship. Baldwin, who supported the move, remembers: “At first, we felt we had better keep talking to them, have dinners with the editor of the Sun. Ed would have drinks with Dacre. Then phone-hacking happened …” Miliband reacted to the scandal by attacking the tabloids’ political influence, and calling for them to be properly regulated. “There weren’t ever drinks with Dacre after that,” says Baldwin. “Dacre was screaming down the phone at Ed. It felt liberating, exciting, scary. Gordon Brown said to us, ‘This is a big thing you’ve done. You’ve got to keep your foot on their neck, or they’ll come back up and smack you.’”

Yet as often with Miliband, his anti-tabloid initiative petered out. “Ed’s management style is to balance,” says a former adviser, “and there were some good personal relationships in the Labour team with some tabloid reporters.” Baldwin says: “We lost the [internal] argument. We got back to business as usual.” At the 2015 election, the tabloids tore into Miliband and Labour regardless.

During the Cameron governments, it felt like Murdoch and Dacre were the adults, and the politicians were children

David Cameron underwent a similar experience with the papers. At first, as Tory leader – influenced by his adviser Steve Hilton, who believed that in the digital era the views of newspapers were of increasingly minor relevance – Cameron decided that rather than “sucking up to Murdoch”, as one of his aides put it, it was better to “keep your distance” from the tabloids, and to focus instead on television appearances. Yet when the effectiveness of Cameron’s leadership was widely criticised in 2007 – not least by Murdoch’s papers – he quickly changed his approach. He hired the former News of the World editor Andy Coulson as his director of communications, and maintained a high-profile, highly political friendship with the editor of the Sun and Murdoch favourite, Rebekah Brooks. In 2009, the Sun switched its support from Labour back to the Conservatives.

Despite Coulson’s resignation over phone-hacking in 2011, and conviction for the same offence in 2014, Cameron’s governments remained tabloid-friendly throughout, straining to come up with populist policies and language.But while the Mail backed the Conservatives as always, Dacre and his paper remained lukewarm towards the metropolitan Cameron. And when Cameron finally challenged the tabloids’ worldview, the EU referendum, they were brutal towards him, and helped terminate his premiership.

Baldwin says, “I’ve been amused to hear Craig Oliver”, Coulson’s successor as Cameron’s communications director, “raging to left-of-centre journos about the rightwing press and how awful they are.” Yelland argues that the tabloid barons are simply “better at what they do than the politicians. Murdoch and Dacre have been around for so long, fashioning words and campaigns. During the Cameron governments, it felt like they were the adults, and the politicians were children.”

Will the reign of the tabloids ever end? It was interrupted when the second world war created a kinder Britain, and again, fleetingly, after the phone-hacking scandal in 2011. Profound social change, or the exposure of journalists’ excesses, can weaken even apparently impregnable tabloid citadels.

Over recent decades, shifting public attitudes have undermined some of the papers’ certainties. “When I look back at the words I used to use as a Sun sub,” James Alan Anslow remembered, “‘the gay plague’, ‘black gangs’. You’d get sacked if you used those now!”

Charlie Beckett detects a hard-nosed rationale behind this softening: “In a tightening market, you don’t want to put off readers. When you had a circulation of four million, it mattered less if you said something racist, say, and put off 5% of your readers.” Moreover, the tabloids have sometimes received disproportionate credit for their liberal moments. The Mail’s much-praised campaigning for the truth about the racist murder in 1993 of the black teenager Stephen Lawrence sits uneasily with the endless xenophobic nudges of its immigration coverage.

The tabloids still look much the same now as they did three decades ago. Redesigns have been much rarer and more cautious than at other papers. So have alterations to the basic tabloid prose style. “You know what you’re going to get from the first sentence,” says Beckett. “They haven’t caught the conversational tone of the internet … their style is very clunky.” David Deacon of Loughborough University says that in his research on election bias he finds that “People are far more aware [now] of the narrative games, of tabloid-speak.” The tabloids have always been self-conscious – “It’s The Sun Wot Won It” – but nowadays their political rages would be almost camp, if they did not have such consequences. As Baldwin puts it, the papers often read “like a parody of themselves”.

Anslow, who is 65, said he sometimes sensed a nostalgia in the air at the Sun’s offices. “If we do a special front page, people say, ‘It’s a real classic. It’s just like the old days.’”

Two years ago, the paper moved from its old premises in east London, an intimidating compound of hulking, almost windowless blocks behind high-security fences, widely known as “Fortress Wapping”, to a much blander, more generic office building in central London. Its glass-walled, approachable-feeling lobby faces directly on to the street. Down one side are blown-up photographs from various Murdoch publications. The Sun’s is just a generic showbiz shot, as if the paper’s political coverage is less of a priority nowadays. On the Sun and Mail websites, political stories are much less prominent than in their print editions.

Meanwhile, the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn is 14 months into an experiment in ignoring the tabloids. It may well be doomed; but his leadership has already lasted longer than the tabloids expected, and their ceaseless attacks on him, like their shouting down of anyone who doubts Brexit will be a success, have a small undertone of anxiety about them.

Twenty-four years ago, the British political scientist Ken Newton pondered the multilayered puzzle of how newspapers and their readers relate politically, and produced perhaps the closest thing to an answer. “The press and its readers are likely to be mutually dependent,” he wrote, “influencing each other in a constantly shifting process of mutual adaptation.” The tabloids may have adapted – a little – to their readers’ changing attitudes, but the papers retain an old-fashioned suspicion of new kinds of Briton, and a nastiness towards people who do not fit their rigid worldviews. Above all, the tabloids remain stubbornly attached to the optimistic free-market ideas of the one prime minister that they have never turned against, Margaret Thatcher – an optimism that many of their readers have not felt since at least the 2008 financial crisis.

This autumn, both the Sun and the Mail have responded to what the Mail’s owner called a “challenging market” for newspapers by making editorial redundancies. A Sun journalist emailed me: “Just had massive compulsory redundos in editorial. Hardly enough bodies left to get out the paper. Mood is of the post-apocalyptic variety – survivors staggering around dazed and confused.”

Anslow, who started on the Sun 39 years ago, was one of those culled. Well before it happened, he told me he could imagine a Britain without tabloids “within my lifetime”. He went on: “If you take that kind of political communication away, we [Britons] will all go into our own ideological silos, because of the way social media works.”

More surprisingly, Tom Baldwin also fears that if the tabloids die, then what comes next could be worse. “Their political stories contain at least kernels of truth,” he says. “Without the tabloids, we’ll be in a totally post-truth world.” But in a world without tabloid truths, perhaps other kinds of politics will have a chance.

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.

• Producing in-depth, thoughtful, well-reported journalism is difficult and expensive – but supporting us isn’t. If you value the Guardian’s independent journalism, please help to fund it by becoming a Supporter.