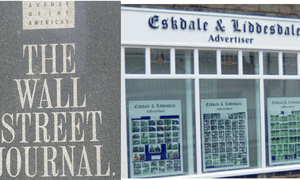

What have the Wall Street Journal and the Eskdale & Liddesdale Advertiser got in common? Or perhaps that question should be: what have the Journal’s owner, mighty News Corporation, and the Advertiser’s owner, the modest CN Group, got in common?

The Journal sells __more than 1m copies a day in print while the Advertiser manages about 1,200 newsprint sales a week.

But the crisis facing both newspapers and their publishers is exactly the same: their business model, which is based around advertising revenue, is in the process of being destroyed.

In fact, in the Advertiser’s case, the past tense is __more relevant. After 168 years of publication, it is losing money and staring closure in the face.

CN Group, the small Carlisle publishing organisation, cannot justify producing the paper any longer and is asking for someone to come forward who is willing to take it off its hands.

If it can’t find a buyer (and it is seeking only a “nominal” sale price) the paper will be closed next month, leaving the people of Langholm and its surrounding hinterland in Dumfries and Galloway without their paper.

CN is hoping for a “community benefactor” to emerge and has asked for people, a group of people perhaps, to contact them. If not, the last issue will appear on 14 December.

There is no existential crisis of that sort at News Corp’s Wall Street Journal, of course. At least, not yet. But the situation at the New York title is certainly dramatic.

Last month, the Journal’s editor-in-chief, Gerard Baker, announced that a “substantial number” of staff would be required to take to voluntary redundancy packages.

By 2 November, with 48 people having already accepted the deal, it emerged that the Journal’s section covering Greater New York was being folded into the paper’s broader coverage of the city. That threatened the jobs of a further 19 staff.

Other separate sections were also consolidated as part of a downsizing exercise which came against a background of falling ad income. More journalists, inevitably, will be going in the coming months.

That is the continuing story at all newspaper companies in both the UK and the US. From British publishers, such as Johnston Press, Trinity Mirror and the Guardian to American publishers, such as the New York Times, Gannett and McClatchy.

According to a recent analysis, for the Columbia Journalism Review by Washington Post writer Pete Vernon, national print advertising in the States has fallen by 35.1% over the year. He wrote:

“Print advertising, still the most lucrative revenue source for most newspaper companies, is in a freefall. The cash cow has steadily declined for years, but 2016 has seen an acceleration in the departure of ad dollars.”

He pointed out that between 2010 and 2015, there had been “a relatively stable decline” of print advertising (between 5-8% each year, according to the Pew Research Center).

But a predicted 11% fall in advertising this year “now seems optimistic.” Why? Because “with shrinking circulations and an inability to provide the targeted marketing and detailed analytics of options such as Google and Facebook, print just isn’t as enticing to advertisers.”

That’s it in a nutshell. The digital giants are sucking up advertising, which is threatening the viability of newspapers. More pertinently, and much more significantly, it is threatening journalism itself.

That’s why I support the call by the Media Reform Coalition (MRC) and National Union of Journalists to impose a 1% levy on the operations of Google and Facebook in order to fund public service reporting.

As I reported on Tuesday, the MRC believes public interest journalism is in peril and, in company with the National Union of Journalists, it hopes to persuade politicians to include an amendment to the digital economy bill in order to create the levy.